This is the sort of nerd obsession that my family has to put up with.

On my birthday in 2019, I knelt down on a grassy hill on Antelope Island jutting out into the Great Salt Lake in Utah, and pulled from my pack a stack of electronic gear and snaking cables. Although the clouds had crept down upon me for the past few hours, the island’s rocky summit that I had climbed hours before could still be seen behind me, as well as the vast expanse of the Great Salt Lake extending to the distant horizon blanketed by rain and mist.

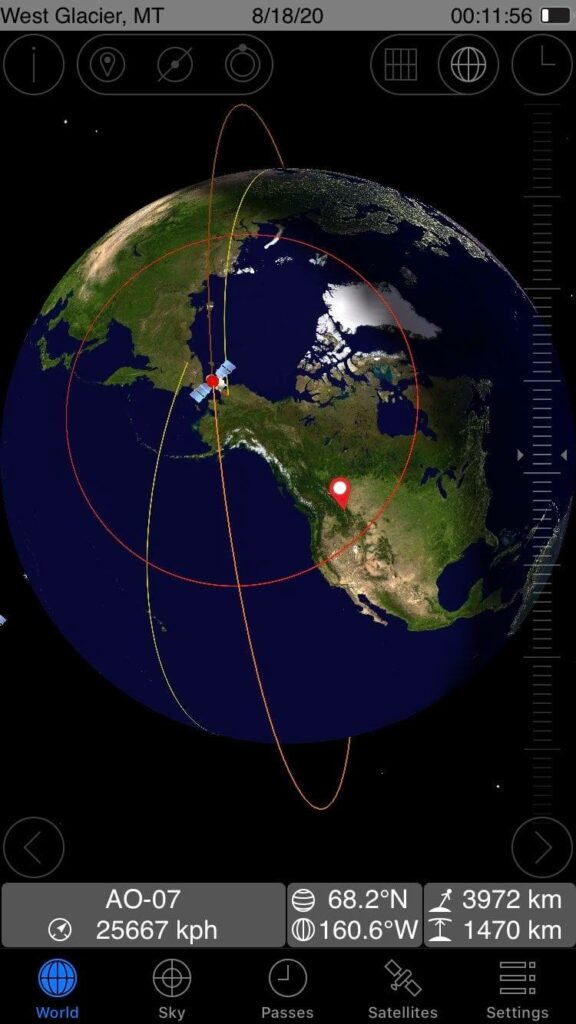

There was one thing I could not see, except in my mind’s eye. Down below that distant horizon and 900 miles out in space, a nearly derelict satellite was careening toward me a 17,000 miles per hour. Also in a very distant place, there was a man in Kamchatka (that remote and exotic locale in far Eastern Russian, from which you can invade via Alaska in the board game Risk) who had just trudged through a light April snow from his house in the town of Yelizovo to go to his radio shack in his garden. The man who I call “The Russian”—his real name is Nikolay or just Nick—sat down at his workbench and powered up his rooftop rotors, swinging his antennas East to point across the International Date Line and up into space. The glow of his radios and the smoldering cigarette in the ashtray on the bench lit a face rapt in attention as he listened for the faint sign of life of the ancient satellite.

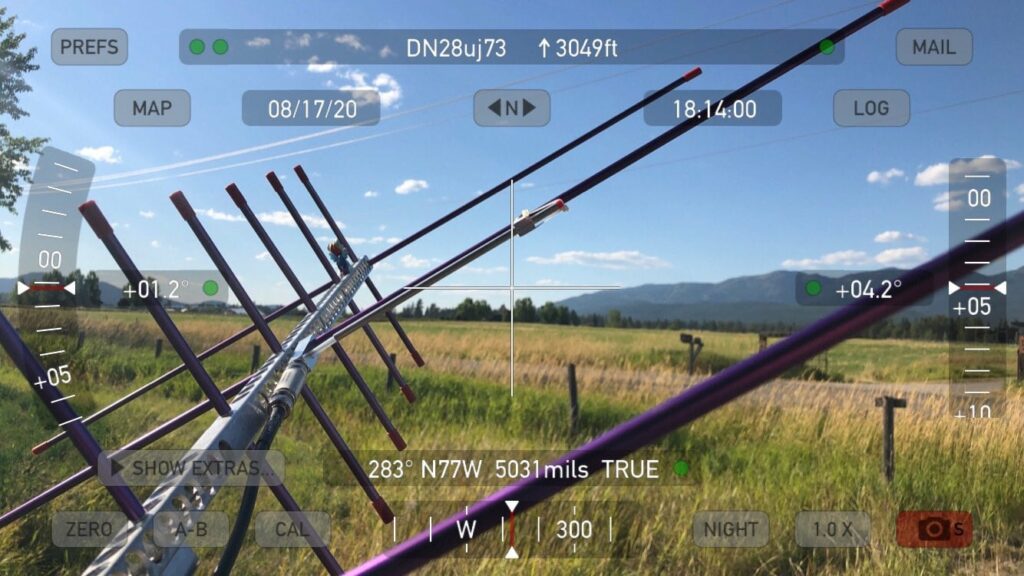

On that grassy hill back in Utah, I worked very quickly to assemble my portable antenna and connect my radios, rain dripping down off my face as I hooked up the cables, strapped the bulky radios onto my chest, and stood to raise the antenna skyward like some late Victorian ideal of a futuristic radio operator. I had been slower than I liked, and though I couldn’t see it, the satellite had cleared the horizon a minute ago. I only had a few precious minutes to listen for The Russian and respond to his radio calls.

Spinning the dial slowly across small band of frequencies, I heard the telltale hiss and pop of radio waves containing a subtle fingerprint of artificial technology beyond the random static of background radiation lingering from the Big Bang. The ZombieSat had awoken today! Listening intently for a stretch of moments, I finally heard a voice, distorted and fading, but a victorious deep booming coming down from orbit and into my ears. “United America Zero Zulu Golf X-Ray,” the voice said in a deep and booming Russian accent. “CQ satellite. This is United America Zero Zulu Golf X-Ray.” It was UA0ZGX—Nick!

It was the first time I had heard his voice. My hand shaking, I held the dripping antenna over my shoulder in the direction of the satellite that had arced well past the zenith point. Microphone raised to my lips, I responded quickly, “United-america-zero-zulu-golf-xray, this is Kilo Zero Fox Fox Yankee.” Silence. I could not hear myself come back down from the transponder in space, which meant that Nick could not hear me either. Damn!

It tried again. Nothing. I checked cable connections and spindly antenna elements. Dripping with rain, it was too wet. Just too wet. All the while, The Russian was repeating his call while the satellite flew swiftly toward the horizon and fell into a silence that was final. I had suffered another failed attempt to contact The Russian. Dejected and yet still invigorated by a beautiful day of hiking up Frary Peak on Antelope Island, I packed back up my antenna and radios, and headed back down to the trailhead and car.

The Russian and I are in a small band of radio nerds dotted sparsely across the globe that use a scattering of satellites in low Earth orbit that contain radio repeaters and transponders. These satellites allow the shared use to those that know the varous nerd spells and incantations. As happens in nerd subcultures and the obscure hobbies they spawn, this happy band puts great importance on things which the larger world has no interest or understanding, going to great lengths to collect radio contacts from far off places via these orbiting satellites, similar to collecting all species and varieties of Pokémon. For example, one steely-nerved and determined individual in this hobby flew his plane from Juneau out into the Bering Sea, to land on an abandoned US military airstrip on one of the farther in the string of the Aleutian Islands (and hoping the runway asphalt survived the past winter’s freeze), so that he could land with his radios in tow, and talk to us on some satellites and hence check off this extremely far-flung locale on our personal maps. On another day a French gentleman stands on a mountaintop lookout in the Pyrenees, pointing his antenna westward toward the waning glow of the setting sun, while at the same moment a fellow operator stands on a 12,000 foot summit in Colorado in the bright midday sun, antenna pointed East toward the Zombiesat in orbit with the goal of making a radio contact from the Colorado Rockies to France and breaking the distance record of two humans trading words using the ZombieSat. I myself took part in these activities while standing in a field outside of Rekjavik in July with a couple of Icelandic horses as companions, and faced toward the Atlantic with antenna raised high, speaking to a dozen people across Europe and North American so that they could add Iceland to their meticulous collection.

For my own collection, I had been trying for more than a year to contact the Russian.

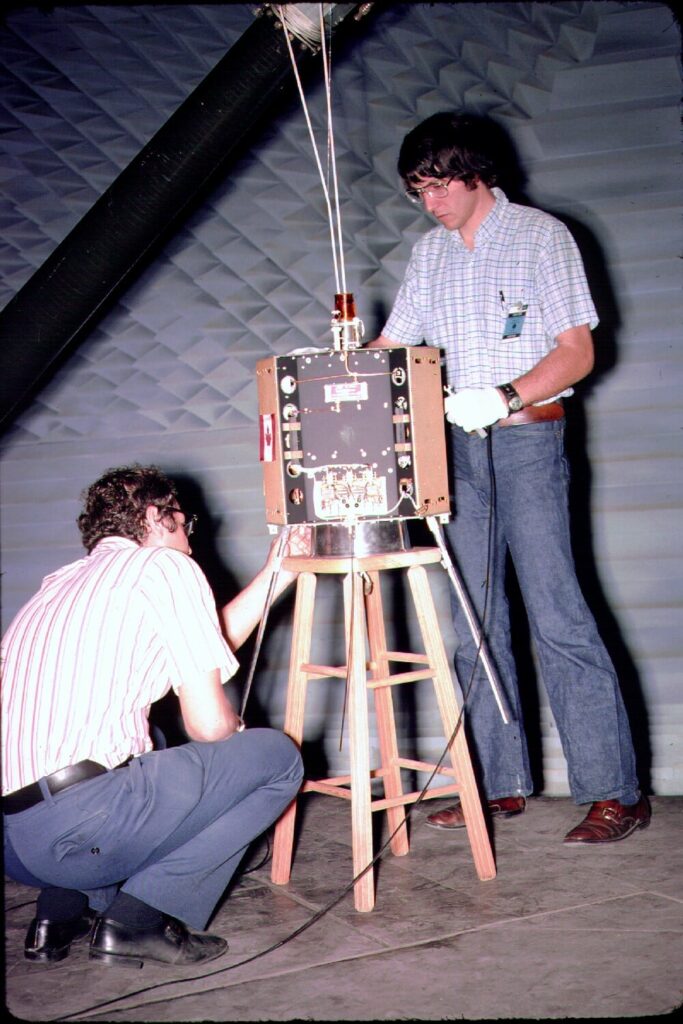

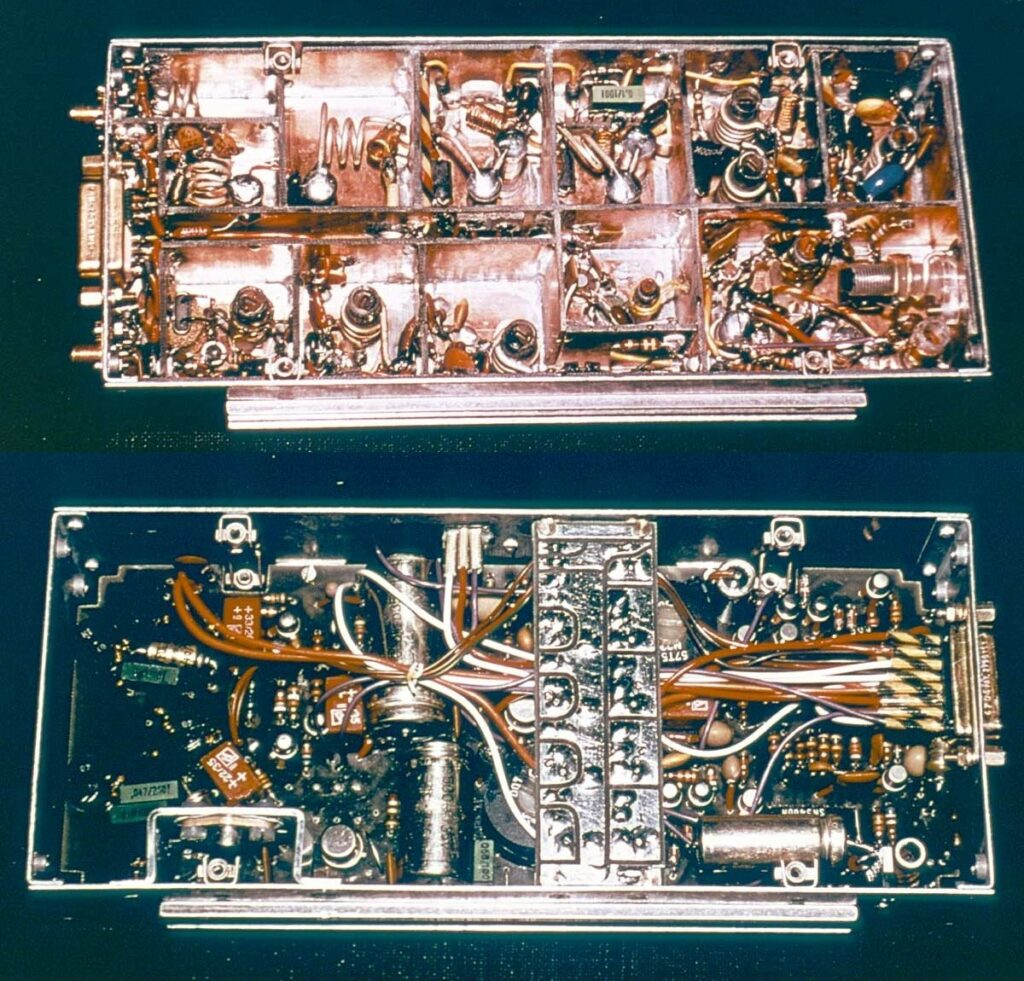

As to the ZombieSat, its actual name is OSCAR-7. OSCAR stands for Orbiting Satellite Carrying Amateur Radio. OSCAR-7 was built by a few men and women in 1973. As with new technologies of that era, it was built in someone’s basement on a wooden bench with commonly available materials for the time. I have seen pictures of it assembled and soldered together painstakingly, by a guy in a polyester shirt and horn-rimmed glasses, using electrical components that by today’s standard are downright primitive. But that is in large part why it is still alive at all yet today! Those big chunky transistors and fat circuit board traces are far more resilient to the harsh radiation filled enviroment of low Earth orbit than any modern microcircuitry could be.

OSCAR-7 was launched in November 1974, at the height of the Space Age and before I was born. Amateur radio enthusiasts happily used it until 1981, when it died a commonplace death of battery failure. That would have been the end of its life story…but…in 2002 another amateur satellite hobbiest heard a radio signal on a frequency where there should be nothing transmitting with the telltale signature of Doppler shift that marks an object in orbit. After days of listening and tracking this occasional signal, he realized that it was OSCAR-7 back from the grave! And so it joined a small collection of zombie satellites as well as the impressive feat of being the oldest operating (active two-way communication) satellite in Earth orbit, even including all unclassified military satellites from the 60s and 70s.

Nowadays, OSCAR-7 still wakes up on most orbits. Whenever it emerges out of the Earth’s shadow and the intense sunlight of space orbit kisses its solar panels, the miracle that caused its batteries to short open sometime between 1981 and 2002 allows electrical energy to flow into its circuitry. Its radio signal is weak, the audio is terribly noisy, and too much radio power used by operators can overload its circuitry and flip it off altogether, but despite all of this, dozens of people use it to talk to each other almost every day. Someday it will turn off for good into a long cold sleep, but for now it’s a great thrill to use this orbiting relic to talk briefly with people within its 8,000 kilometer radio footprint. I have used it to contact people in Alaska, a Canadian Artic research station in Nunavut, Greenland, Britain, Finland, Germany, France, Spain, the Canary Islands off Africa, Brazil, Ecuador, Hawaii, and finally in summer of 2020: Kamchatka!

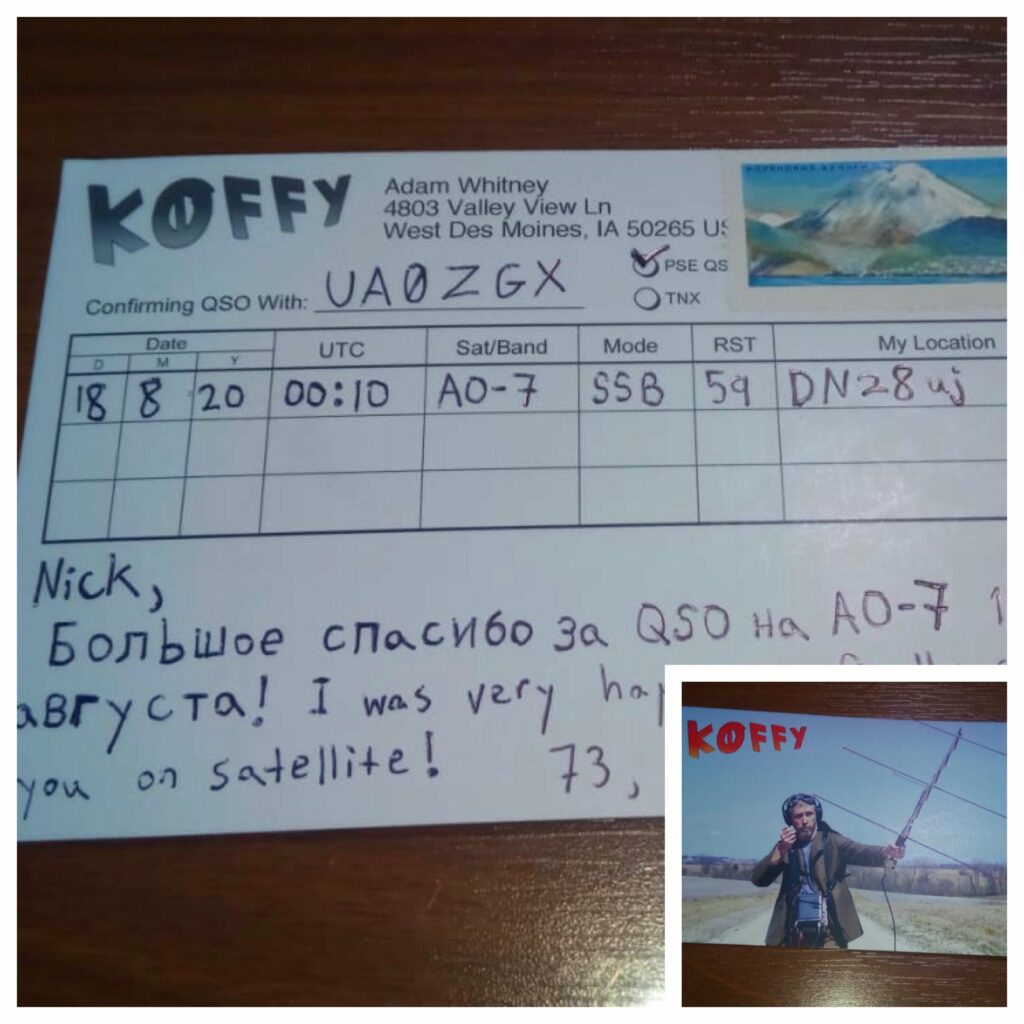

While in Montana in August of 2020, I finally contacted The Russian. It was a sweet victory after so many attempts, and I was grateful to Nick who had been very patient with me for almost two years. The giant, snow-capped twin volcanoes that dominate the sky above the city of Kamchatka Kraai and the Yelizovo township make it difficult for us to exchange radio signals via an orbiting satellite from this distance. For every trip I made of any significant distance to the North or West, I would fire up WhatsApp in the airport on the day before and send a message to Nick’s phone in Kamchatka. Thanks to Google Translate, we’d have exchanges in a hybrid Russian/English/satellite nerd lingo, back and forth, with him often responding when I was sleeping and vice versa, with his clock 6 hours behind on the other side of the International Date Line. Nevertheless, he humored me for two years, with my favorite response: “Yes, AO-7 at 23:07 UTC. QRG 145.938. I go to radio room at that time.” I’m probably on some sort of goverment list at this point, always contacting Russia while traveling through airports across the country.

A few months ago after making the satellite contact with Kamchatka, I finally received my trophy. A QSL post card from Katchatka. QSL is old school radio lingo from the Morse code days means “confirming contact”. Three months prior, I had sent my postcard requesting a reponse. Even via airmail the post travels slowly to Kamchatka, especially during the COVID pandemic.

I got to practice my Russian, painstakingly writing the cyrillic block characters that expressed my gratitude, and I included a collection of 1965 Soviet era stamps I found for sale online and shipped to me from Moscow, which feature the larger Кроноцкая сопка volcano that rises above him out his window and I knew was pictured on his own QSL postcard.

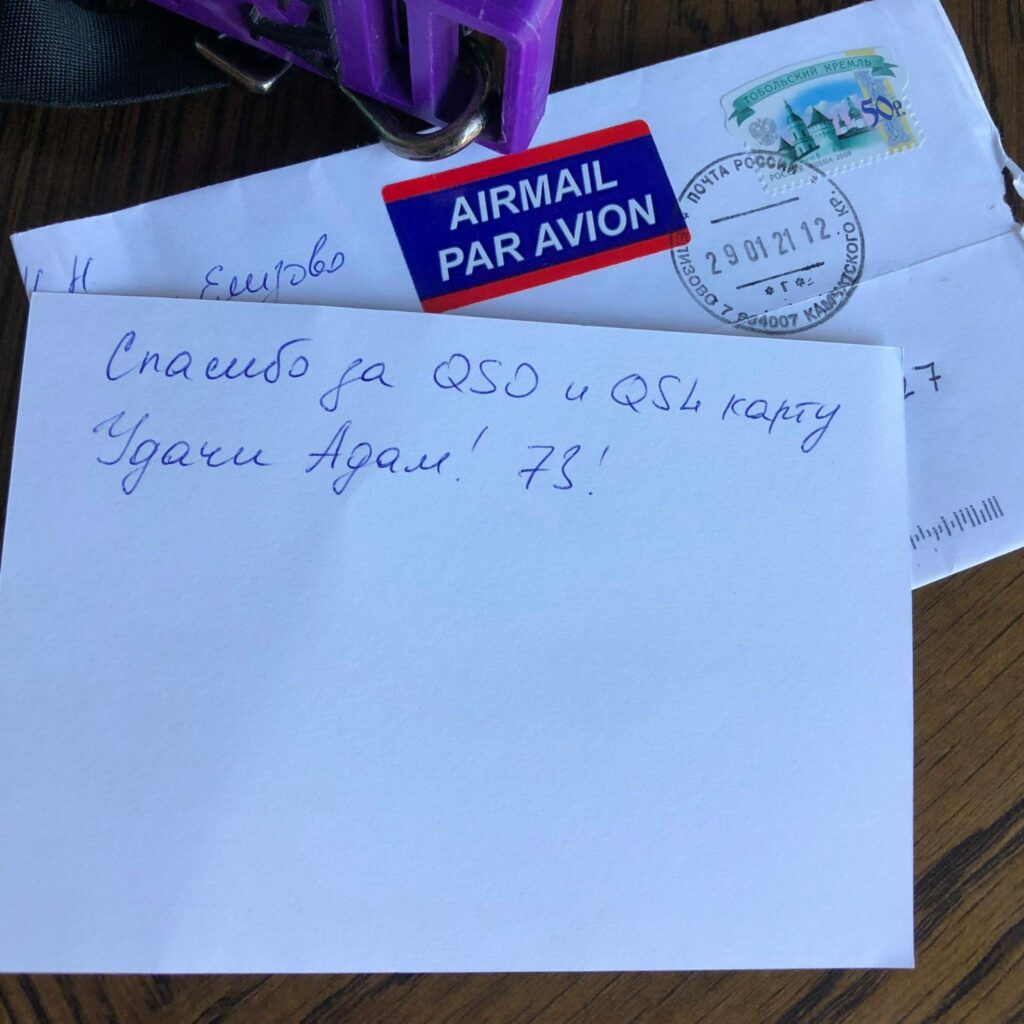

In February, I was thrilled to see in my mailbox a letter from Kamchatka! It took me an hour to decode his cursive, handwritten cyrillic into the message to me: “Спасибо за QSO и QSL карту. Удачи, Адам! 73!” The translation: “Thanks for the QSO and QSL card. Good luck Adam! 73!”

I don’t listen to the ZombieSat much these days now that I’ve chalked up the crazy nerd achievement of contacting many other crazies in all the reachable continents: North America, South America, Oceania (Hawaii), Africa (Canary Islands), Europe, and Asia (Kamchatka). But when I do, it is still a great thrill to be able to wake to life a relic of our technological ingenuity in space that flies above our heads every day, and I remember the times I would listen to its signals for the voice of The Russian.

The “The Late Victorian Ideal of a Futuristic Radio Operator” picture should be an ARRL magazine cover. Love it

My Iceland photo did make the cover of one ARRL publication, so I don’t feel like I can ask for too much more!