The science fiction Culture novels by Iain M. Banks, a series of 10 books published from 1987 to 2012, has become widely known of late, thanks in part to SpaceX naming their autonomous drone ships after some of the sentient Culture ships in memoriam of Banks who passed away in 2013. I first encountered the books myself in 2016 after a mention by fellow Scottish author Charlie Stross. I read the final book The Hydrogen Sonata first, before making my way piecemeal through the series in subsequent years.

This summer, I read the 7th book Matter for a second time, and I had one of those moment that every reader seeks, where the deeper meaning clicks into place in your head. Many of the unanswered questions I had about the series, and in particular the hints that Banks had encoded into the warp and weft of the stories, suddenly became apparent. Afterward, I spent several days in a sort of intellectual fugue pondering this wisdom printed on a dead tree by a dead man about ideas as timeless as the Culture itself.

If you are not familiar with these books, Wikipedia describes the Culture series as “a utopian, post-scarcity space society of humanoid aliens and advanced superintelligent artificial intelligences living in artificial habitats spread across the Milky Way galaxy. The main themes of the series are the dilemmas that an idealistic, more-advanced civilization faces in dealing with smaller, less-advanced civilizations that do not share its ideals, and whose behaviour it sometimes finds barbaric.” This is certainly fertile ground for thought experiments, especially in one subject in particular: how humanity would fare in a post-scarcity world enabled in large part by superintelligent AI, a future that no longer appears so totally far-fetched from where we stand in 2022.

This seems to be the primary itch that Iain Banks needed to scratch. How would we fare? In order to answer this, Banks builds a spectacularly creative and richly immersive universe to explore the subject of humanity unfettered by so many constraints, and through this he sets about presenting variations on this theme, exploring what dilemmas remain when so many others have fallen away. The final effect is to provide the reader with a lens to discern the commonality in the human experience, regardless of our constraints, with the ultimate goal of clearing away enough fog to see what’s what and what to do about it.

Now, before you read any further, I encourage you to close your web browser, forget about this blog, and instead read the books yourself. I have absolutely no bona fides for explaining a literary work beyond taking a Victorian Literature class in college, suffering through Sartor Resartus, and being the unwitting tool by which the professor would berate the English majors with statements like, “You see this CompSci guy in the front row? He seems to be the only student in the room who has read the Elizabeth Barrett Browning poem, let alone understood it.” That said, if you ignore my advice to turn aside now, here’s my take on Iain Banks’ answers to the many questions posed by the Culture series that he has woven into the novel Matter.

Now, place yourself into a future where nearly every barrier against humanity has fallen away. Not just your biological sex, but every imaginable aspect of physical form can be transformed. Bodies can be modified or augmented to withstand extremely hostile physical environments. Disease, pain, and aging are all things of the past. Even death itself by destructive means is largely just an inconvenient and temporary state, overcome by reinstating a backup of your mind from any prior moment and decanting into a exact copy of your body.

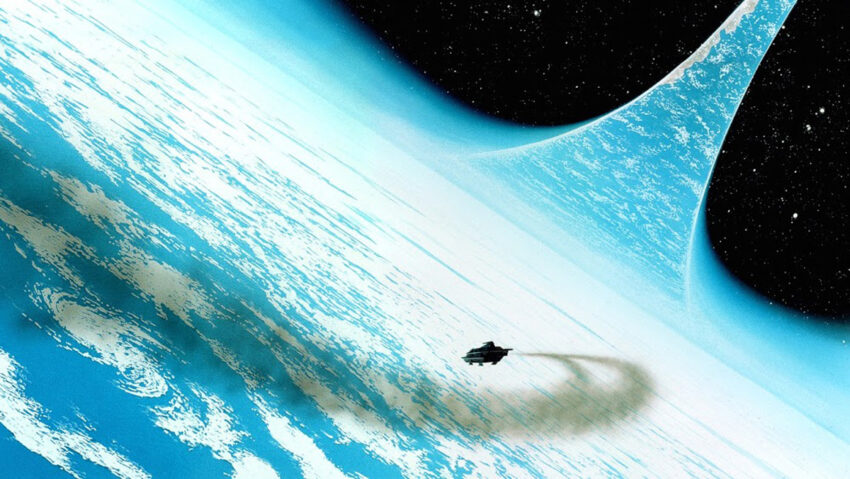

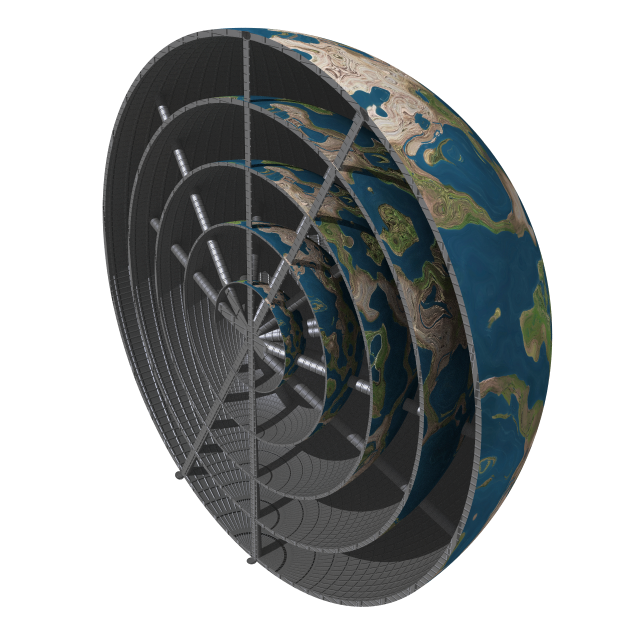

Technology created by humans, most specifically artificial intelligence, has long since surpassed our capability to understand or to control it. Rather than supplanting humans in the evolutionary sequence, however, the superintelligent AIs, or Minds as they are called, have formed a society (the Culture) alongside their human creators, in which the Minds act as largely benevolent protectors. The Minds control every aspect of the environment in which humans live, the most popular of these being Orbital space habitats and planet-sized spaceships that are home to billions of people. Minds possess if not an utter control of the physical universe, then they certainly have a deep fundamental understanding of it, resulting in the Culture having nearly god-like powers when it comes to science and tecbhnology. All planning, production, and administration is done by the Minds, leaving humans to lives of complete freedom to pursue any passion or pleasure that their hearts desire.

At this point, as readers are led through this universe following the stories that unfold in the series, we form many questions. First, as a human with no real inherent impetus in your existence, not even in survival against death, what purpose remains? The pursuit of passions and pleasures certainly only lasts so long, and then what? What do you do now?

Second, what about the Minds? What use at all do they have for the humans? In a society of these Minds and their interactions with other alien superintelligent beings in the universe, why remain with the humans? Why house and protect them? Why involve yourself with them at all? Certainly at best humans are like simple pets, at worst a primitive life form of passing interest. And yet, even the Minds themselves are not all-powerful. They do not see or know everything, they endure doubts and conflicts, they suffer defeats and destruction. They are so incredibly advanced, and still on the grand universal stage, the Minds remain as ultimately vulnerable as humans.

In so many senses, humans have passed the torch to their superhuman AI creations, the Minds, but despite their vast powers they face the same existential questions as their more primitive creators. Why do the Minds choose to endure?

All of the elder beings that have existed in the billions of years of the galactic past have either vanished, presumably to a final destruction and death of their species, have descended into barbarism starting the cycle all over again, or have Sublimed, which means to have taken the final act of departing from the realm of individual consciousness in this material universe to a incorporeal and collective existence. This act of sublimation is mostly seen by the Culture as both a tempting escape to “a better place” but also with a healthy does of suspicion as to its true nature. At the very least, Banks seems to suggest two bookends on the spectrum of civilization, extinction as a disintegration into full entropy and sublimation as a transcendence to a harmonious state of nearly zero entropy where a single perfect chord plays forever without very much else ever happening again.

As I read the books in the Culture series, I mostly wanted to just explore this universe and be taken through the fun and often extremely weird stories that Banks was telling. I put aside these questions and suspended my disbelief in order to enjoy the ride. At some point in reading the series, however, you begin realize that Banks’ intellect has set out to understand these problems, and that he is working out the answers himself as he explores this universe. The results have been recorded onto the pages of the book in your hands should you choose to seek them.

An answer to the existential dilemma, for humans and Minds alike, is first presented in the Culture organizations called Contact and Special Circumstances, which are central to the plots in the series. Contact is like the busybody chuch lady of the Culture, whose role is to watch, interact, and in some cases intervene in the affairs of other civilizations, with the intent of directing the course of these civilizations toward a galactic harmony instead of conflict. Special Circumstances (SC) steps in when the knowledge or moral uncertainty exceeds the capabilities of Contact. There are several books where, stated or implied, both of these organizations provide the driving purpose to the Culture, a sort of do-good-works directive that benefits both themselves and other civilizations. This is indisputably true, even in their language where the Culture refers to all active space-faring civilizations in the galaxy as the Involved or In-Play, but it is also glaringly obvious that only a small subset of the humans in the Culture belong or participate in the activities of Contact or SC.

This rankled, and in book after book I wondered if Banks had ever adequately answered it. Or, more likely I had just not understood what he was trying to say. And here we come to 2022, where as an older and perhaps wiser human, I read Matter for a second time. I had stopped seeking the answers and wanted only to enjoy a great story. Despite this, my stupid brain would not sit quiet, and I saw the glimpses of what Banks was endeavoring to reveal.

This, intrepid reader, is where we tread deeper into these questions of philosophy, which according to Prince Ferbin in the book is “a field of human endeavor [of which the] principal purpose was to prove that one equalled zero, black was white, and educated men could speak through their bottoms.” Well, no matter. Summoning at least as much courage as Iain Banks, I will continue and say that I could find answers (that satisfied me at least). In the book Matter, the primary vessels for Banks’ message are the words of ex-Culture agent Xide Hyrlis and Prince Oramen, and most especially in the final choices and actions of Prince Ferbin, Choubris Holse, Djan Seriy Anaplian, and the Mind of the ship Liveware Problem.

Let’s start with Xide Hyrlis, definitely a character that stands out in the vast cast of Culture heroes and weirdos, who when he is finally located gives Ferbin and Holse the most clear explanation of motives of the Culture as can been seen in perhaps the whole series. In this exposition, Hyrlis presents his own existential dilemma regarding the nature of reality, and how he has come to deal with it.

“You know there is a theory,” Hyrlis said quietly, walking amongst the gently glowing coffin-beds, Ferbin and Holse at his rear, the four dark-dressed guards somewhere nearby, unseen, “that all that we experience as reality is just a simulation, a kind of hallucination that has been imposed upon us.” …

He nodded at the unconscious bodies all around them. “These sleep, and have dreams inflicted upon them, for various reasons. They will believe, while they dream, that the dream is reality. We know it is not, but how can we know that our own reality is the last, the final one? How do we know there is not a still greater reality external to our own into which we might awake?”

“Still,” Holse said. “What’s a chap to do, eh, sir? Life needs living, no matter what our station in it.”

“It does. But thinking of these things affects how we live that life. There are those who hold that, statistically, we must live in a simulation; the chances are too extreme for this not to be true.” …

“There are always people who can convince themselves of near enough anything, seems to me, sir,” Holse said.

“I believe them to be wrong in any case,” Hyrlis said … “If we assume that all we have been told is as real as what we ourselves experience – in other words, that history, with all its torturings, massacres and genocides, is true – then, if it is all somehow under the control of somebody or some thing, must not those running that simulation be monsters? How utterly devoid of decency, pity and compassion would they have to be to allow this to happen, and keep on happening under their explicit control? Because so much of history is precisely this, gentlemen.”

They had approached the edge of the huge space, where slanted, down-looking windows allowed a view of the pocked landscape beneath. Hyrlis swept his arm to indicate both the bodies in their coffin-beds and the patchily glowing land below.

“War, famine, disease, genocide. Death, in a million different forms, often painful and protracted for the poor individual wretches involved. What god would so arrange the universe to predispose its creations to experience such suffering, or be the cause of it in others? What master of simulations or arbitrator of a game would set up the initial conditions to the same pitiless effect? God or programmer, the charge would be the same: that of near-infinitely sadistic cruelty; deliberate, premeditated barbarism on an unspeakably horrific scale.”

Hyrlis looked expectantly at them. “You see?” he said. “By this reasoning we must, after all, be at the most base level of reality – or at the most exalted, however one wishes to look at it. Just as reality can blithely exhibit the most absurd coincidences that no credible fiction could convince us of, so only reality – produced, ultimately, by matter in the raw – can be so unthinkingly cruel. Nothing able to think, nothing able to comprehend culpability, justice or morality could encompass such purposefully invoked savagery without representing the absolute definition of evil. It is that unthinkingness that saves us. And condemns us, too, of course; we are as a result our own moral agents, and there is no escape from that responsibility, no appeal to a higher power that might be said to have artificially constrained or directed us.”

Hyrlis rapped on the clear material separating them from the view of the dark battlefield. “We are information, gentlemen; all living things are. However, we are lucky enough to be encoded in matter itself, not running in some abstracted system as patterns of particles or standing waves of probability.”

Holse had been thinking about this. “Of course, sir, your god could just be a bastard,” he suggested. “Or these simulationeers, if it’s them responsible.”

“That is possible,” Hyrlis said, a smile fading. “Those above and beyond us might indeed be evil personified. But it is a standpoint of some despair.”

Banks, Iain M. Matter (A Culture Novel Book 7) (pp. 338 – 340). Orbit. Kindle Edition.

Hyrlis posits that the cold unthinking nature of physical reality, including the brutal reality of a biological existance, provides evidence that reality is in fact real “matter in the raw”, and therefore the actions of all concious beings are truly free according to their will, and the ultimate responsiblity in choosing compassion or cruelty, help or harm, the choice of good or evil is ours and ours alone.

Then, however, Banks creates a contradiction. Hyrlis next goes on to explain that he left the Culture and Special Circumstances to become a free-agent, his goal being to help reduce the suffering of the combatants in a devastating planet-wide war that has been manufactured by the Nariscene aliens, a species that glorifies war and takes pleasure in watching this barbaric conflict in which Hyrlis is employed.

“And you are proud to take part in what you effectively describe as a travesty, a show-war, a dishonourable and cruel charade for decadent and unfeeling alien powers?” Ferbin said, trying to sound – and, to some degree, succeeding in sounding – contemptuous.

“Yes, prince,” Hyrlis said reasonably. “I do what I can to make this war as humane in its inhumanity as I can, and in any case, I always know that however bad it may be, its sheer unnecessary awfulness at least helps guarantee that we are profoundly not in some designed and overseen universe and so have escaped the demeaning and demoralising fate of existing solely within some simulation.”

Ferbin looked at him for a few moments. “That is absurd,” he said.

“Nevertheless,” Hyrlis said casually, then stretched his arms out and rolled his head as though tired.

Banks, Iain M.. Matter (A Culture Novel Book 7) (pp. 344-345). Orbit. Kindle Edition.

The tension of doubt is played like a bow on the strings of the universe. Is reality an existence of conscious beings acting freely according to their own choices? Or is reality in some way a manufactured simulation or a set of contrived circumstances providing merely the illusion of choice?

Near the end of the chapter, however, Hyrlis presents an observation that cuts through his contradiction and seemingly unanswerable question.

Holse nodded at the map. “All this, sir. Is it a game?”

Hyrlis smiled, still looking at the great glowing bubble of the display. “Yes,” he said. “It’s all a game.”

“Does it start from what you might call reality, though?” Holse asked, stepping close to the balcony’s edge, obviously fascinated, his face lit by the great glowing hemisphere. Ferbin said nothing. He had given up trying to get his servant to be more discreet.

“From what we call reality, as far as we know it, yes,” Hyrlis said. He turned to look at Holse. “Then we use it to try out possible dispositions, promising strategies and various tactics, looking for those that offer the best results, assuming the enemy acts and reacts as we predict.”

“And will they be doing the same thing as regards you?”

“Undoubtably.”

“Might you not simply play the game against each other then, sir?” Holse suggested cheerily. “Dispensing with all the actual slaughtering and maiming and destruction and desolating and such like? Like in the old days, when two great armies met and, counting themselves about equal, called up champions, one from each, their individual combat counting by earlier agreement as determining the whole result, so sending many a frightened soldier safely back to his farm and loved ones.”

Hyrlis laughed. The sound was obviously as startling and unusual to the generals and advisers on the balcony as it was to Ferbin and Holse. “I’d play if they would!” Hyrlis said. “And accept the verdict gladly regardless.” He smiled at Ferbin, then to Holse said, “But no matter whether we are all in a still greater game, this one here before us is at a cruder grain than that which it models. Entire battles, and sometimes therefore wars, can hinge on a jammed gun, a failed battery, a single shell being dud or an individual soldier suddenly turning and running, or throwing himself on a grenade.”

Hyrlis shook his head. “That cannot be fully modelled, not reliably, not consistently. That you need to play out in reality, or the most detailed simulation you have available, which is effectively the same thing.”

Holse smiled sadly. “Matter, eh, sir?”

“Matter.” Hyrlis nodded. “And anyway, where would be the fun in just playing a game? Our hosts could do that themselves. No. They need us to play out the greater result. Nothing else will do. We ought to feel privileged to be so valuable, so irreplaceable. We may all be mere particles, but we are each fundamental!”

Banks, Iain M.. Matter (A Culture Novel Book 7) (pp. 347-348). Orbit. Kindle Edition.

In the next chapter, Banks begins another thought experiment. This will be a familiar concept to students of modern physics and the implications that arose from Einstein’s theories and also Quantum Mechanics, which have seeded some excellent science fiction stories in popular culture. In this chapter, Choubris Houlse begins his departure from his typically matter-of-fact and grounded perspective as he starts to reflect on all that he has seen and heard since leaving Sursamen, and he builds upon the idea that life is essentially a game.

The ship had advised them on which games they would find most rewarding and they’d ended up playing those whose pretended worlds were not all that different from the real one they’d left behind on Sursamen; war games of strategy and tactics, connivance and daring.

Holse had taken at first guilty and then unrestrained delight in playing some of these games from the point of view of a prince. Later he had discovered works, analyses and comments related to such games, and, intrigued, started to read or watch these too.

Which was how he came to be interested in the idea that all reality might indeed be a game, most specifically as this concept related to the Infinite Worlds theory, which held that all possible things had already happened, or were happening now, all together.

This alleged that life was very like a game or simulation where every possible course and outcome has already been played out, noted down and drawn up, as though on an enormous map, with the beginning of the game – before a piece has been moved or a move has been made – in the centre, and every single possible end state arranged along the outer fringe of this implausibly stupendous chart. By this comparison, all that one does in mapping out the course of one particular game is trace a path from that central Beginning of things out through more and more branches, chances and possibilities, to one of the near infinitude of Ends at the periphery.

And there you were; the further likeness being drawn here, unless Holse had it completely arse-before-cock, was that which held; As Game, So Life. And indeed, As Game, So Entire History Of Whole Universe, Bar Nothing And Nobody.

Everything had already happened, and in every single possible way, too. Not only had everything that had already happened happened,everything that was going to happen had already happened. And not only that: everything that was going to happen had already happened in every single possible way that it possibly could.

So if, say, he played a game of cards with Ferbin, for money, then there was a course, a line, a way through this already written, previously happened universe of possibilities which led to the outcome that involved him losing everything to Ferbin, or Ferbin losing everything to him, including Ferbin suffering a fit of madness and betting and losing his entire fortune and inheritance to his servant – ha! There were universe-lines where he’d kill Ferbin over the disputed card game, and others wherein Ferbin would kill him; indeed there were tracks that led to everything that could be imagined, and everything that would never be imagined by anybody but was still somehow possible.

It seemed at first glance like utter madness, yet it also, when one thought about it, appeared somehow no less implausible than any other explanation of how things truly were, and it had a sort of completeness about it that stifled argument. Assuming that every branching fork on the universe map was taken randomly, all would still somehow be well; the likely things would always outnumber the unlikely and vastly outnumber the ludicrous, so as a rule things would happen much as one expected, with the occasional surprise and the very rare moment of utter incredulity.

Pretty much as life generally was, in other words, in his experience. This was at once oddly satisfactory, mildly disappointing and strangely reassuring to Holse; fate was as fate was, and that was it.

He immediately wondered how you could cheat.

Banks, Iain M.. Matter (A Culture Novel Book 7) (pp. 386-388). Orbit. Kindle Edition.

In reading these chapters, you see that Iain Banks had laid the foundation stones for why the humans and the Minds of the Culture continue to persevere. The vast and growing knowledge afforded to the Culture through millenia of science and the intelligence of the Minds has its hard limits. There will inevitably be questions that are unanswered, knowledge that is unknowable. In the end, however, none of that matters. Life in a simluation, in the multiverse, or in a true and base reality all has a sufficient amount of complexity and uncertainty that the actions of any conscious individual can and do truly matter, and no power, degree of determinism, or ablity to cheat can ever really change that fundamental truth.

This beacon of truth is what allows the Culture to dispel the darkness of despair and underpins it with a very human degree of hope. Still, to what end or purpose do the humans and Minds of the Culture pursue? What keeps them going?

For this, let the plot unfold and let the characters in the this grand play guide us toward and answer.

A very poetic statement is made by Prince Oramen, very near the end of the book, as he speaks to the ancient and mysterious sarcophagus that is striving to return to life after an near eternity of being buried and dead.

“But all peoples go,” Oramen said gently, as though explaining something to a child. “No one remains in full play for long, not taking the life of a star or a world as one’s measure. Life persists by always changing its form, and to stay in the pattern of one particular species or people is unnatural, and always deleterious. There is a normal and natural trajectory for peoples, civilisations, and it ends where it starts, back in the ground. Even we, the Sarl, know this, and we are but barbarians by the standards of most.”

Banks, Iain M.. Matter (A Culture Novel Book 7) (pp. 519-520). Orbit. Kindle Edition.

“Life persists by always changing,” says the primitive Oramen. An assurance toward action. An embracing of the necessity of change. An admission of the impossibility of absolute preservation. An absolution for the inevitable departure, either by the individual or the civilization. A condemnation against any civilization trying to destroy another completely, and perhaps also a warning against the Sublimed.

In all the Culture books both humans and Minds, when faced with some dire conflict, overcome the fear of an uncertain choice and take actions that they know will result in a change that steps them over the threshold into some uncertain future. This courage is fundamental to the Culture, with Banks projecting the best of human nature far forward into this possible future.

The compass in these choices has a common waystone, and this is seen in no better way in the series than in the final chapter of Matter, where the main characters prosecute the final act battling the mysterious sarcophagus, which turns out to be an ancient planet-killing creation that destroys Shellworlds.

Faced with obviously insurmountable odds in battle, the primitive and cowardly Prince Ferbin, the brilliant Culture agent Djan Seriy Anaplian, and the impossibly intelligent Mind of the ship Liveware Problem, all of these people sacrifice their lives in a final act of compassion to save others from suffering and death.

In the end, both humans and Minds are in the same boat. No matter how far the envelop is pushed in pursuit of complete understanding and control of the situation, there remains always the lurking unknown and the inevitable end. The constant of life, in a post-scarcity ultra-powerful Culture OR here and now, is this. In the sum total of every action in past in the entire universe that led up to this present moment RIGHT NOW, combined with the near infinitude of possibilities that might result from any given action, humans and the Minds alike share the burden of making a right choice in the face of uncertainty and possible destruction. This fundamental constant of human existence, biological or artificial, and the courage to overcome it is what keeps us going now and in our future. Until it ends where it starts, as Prince Oramen says, in the ground returning to the very matter of existence.

© 2022 Adam Whitney